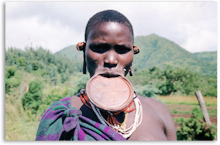

The surma and the Mursi are part of the that small remaining group

of peoples any where in the world whose women still wear lip plates

- and, once again, these have a function that is almost purely

symbolic. There are several theories as to why the use of lip plates

was first adopted: Perhaps to discourage slavers looking for

unblemished girls, or perhaps to prevent evil from entering the body

by way of the mouth (since these people believe that evil penetrates

the body through its orifices); or to indicate the number of cattle

required by the wearers family for her hand in marriage.

Today it is the third of these theories that is the once seen in

practical use. In her early twenties a woman’s lower lip will be

pierced and then progressively stretched over the period of a year –

the size of the lip plate determining the size of the bride price.

A large lip plate will bring fifty heads of cattle. A heavy iron

puberty apron and many armlets will like wise help to increase the

young woman’s appeal.

Between the ages of twenty and twenty five, a lip plate is inserted

into a women’s lower lip. The process begins six months prior to

marriage with the piercing of the lower lip. Successive stretching

is achieved by placing increasingly larger plates into the pierced

lip. The final size of the plate is an indication of the number of

cattle required by the girl’s family for her hand in marriage. Women

make their own lip plates from locally dug clay, color them with

ochre and charcoal, and bake them in a fire.

After six months of stretching, the lip is so elastic that a plate

can be slipped in and out without difficulty. The plates must always

be worn in front of men and can only be taken out at private meal

times. When sleeping or in the presence of other women. In the past

plates were wedge-shaped and made of a balsa wood. More recently

these have been replaced by round clay plates. Unlike lip plates,

clay ear plugs are worn by both young girls and women for decoration

alone.

It would be wrong to suggest that all forms of decoration are

symbolic, however, purely aesthetic considerations, too, are to be

seen at work in the lower Omo notably among the Surma and the Karo.

The best artists are generally male and they paint not just each

other but also the women and children of the tribe using local chalk

mixed with water, they create many and varied patterns including

swirls, stripes, flower and star designs- all of which are enjoyed

solely for their beauty. This activity is one of the main forms of

artistic expression available to the Surma and the Karo creatively

at work. The painter reveals himself as an artist, and the human

form- viewed as a living sculpture and as a vehicle for the

imagination- becomes itself a work of art.

The innocent enthusiasm that body paintings generates, the

inspiration that it expresses, and the close social bonds that it

reaffirms all suggest that the lower Omo is a place of joy and hope

as well as of intertribal competition and war, a place in which

mankind is still capable of appreciating simple pleasures still

filled with laughter, and still unashamedly amazed at the winders

that the world has to offer.

Bumi men decorated their faces with scarified designs to establish

tribal identity and to enhance their physical appearance like the

Hamar, they wear elaborate clay hair buns, symbolic of bravery and

courage. (Tour itinerary)

![]() Decoration; Karo

Decoration; Karo

Decoration is almost a universal phenomenon of mankind. The Karo are

not exceptional. In order to decorate themselves the Karo use

natural resources as well as man made ornaments of various kinds.

They paint their hair a mixture of red soil (Zare) and butter or

castor oil. They commonly wear bracelets, and beads are widely used

for decoration. The girls’ dresses, often made from sheep or goat

skin, are decorated with different things including small nails.

Every one smears his or her body with Seli, a type of soil, for

dancing ceremonies. They also have different types of hair style and

it is quite common to put a feather on their head.

![]() Stool Making (Karo- Borkotta)

Stool Making (Karo- Borkotta)

Karo-borkotta is one legged stool carved from Wanza or Shola tree.

It serves as a seat and head rest for elders. It is a symbol of

higher status and respect within the community. The Karo carry the

karo borkotta around with them, wherever they go. It is prepared by

skilled Karo men. The youth use a three-legged stool (yado-borkota)

until they are fifteen. The yada-borkotta has no other social value;

it si just used as a seat or a head rest. At the age of fifteen the

youth of a village organize themselves and ask Karo elders for

permission to use Karo-borkotta. If elders accept the request the

youths either buy or prepare their own karo-borkotta. To start using

the stool, the youths of the village should organize a ceremony

called sele for the elders and the community to publicize the

permission they are given to use kora-borkotta. The ritual opens the

way for the youth to have equal seat, integration with elders, and

fully participation in the socio-economic and political affairs of

the community.

In addition to its service as a seat and a head rest, the

karo-borkotta symbolizes status and respect.

![]() Local Dress (Koysha)

Local Dress (Koysha)

Koysha is a traditional and indigenous knowledge based sisal-made

mini-skirt which Ari Women wear below the waist. The bast (sisal) is

prepared from the barks of a local tree called Koysha and false

banana. The Ari make the bast shiny and attractive by rubbing it

with locally prepared castor oil and red clay soil. The koysha can

be made by all adult Ari Women, but the most experienced and skilled

produce the best quality koysha. The knowledge is derived from their

ancestors who used it as a mechanism for fulfilling one of their

basic needs (clothing), and for adapting to their environment.

![]() Local Dress (Aye)

Local Dress (Aye)

Aye is made from goat skin and it is decorated with pieces of

metallic ornaments and beads. Karo girls put it on below their

waist. Aye is rubbed with a mixture of red soil and locally

extracted castor oil to be softy and shiny. Girls prepare their own

dresses and decorate them in group. Parents give support by tanning

the skin and giving advice.

This indigenous knowledge of making aye enables the Karo to fulfill

one of their basic needs (clothing) and to compensate for the

inaccessible factory products.

![]() Snake dance

Snake dance

Surma children often point themselves as identical twins. The snake

dance is one of their favorite games. Squatting on the ground, the

children form a long line and hop slowly forward like grasshoppers

singling in unisons the words; “Our mother, our apple, our fruit.”

The Surma live primarily on a diet of milk and blood, seasonally

supplemented by maize and millet. An arrow is shot a quarter of an

inch into the jugular vein of young heifer to obtain just enough

blood to fill a calabash. The animal is never killed; instead the

wound is sutured with a compress of wet mud. Young boys drink blood

to grow, and men to gain strength.

Ethiopian cuisine is unique by way of ceremony, flavor, color and

presentation. First decorated metal or clay water jugs are brought

to the table and their contents poured over the guests’ outstretched

hands into a small bowl below. This cleansing is sometimes followed

by a short prayer of thanksgiving.

The first course, which immediately follows this ceremonial aspect

of the metal, is usually a mild dish such as curds and whey to

cleanse the palate for the spicier offering that follows.

Wot, the national dish, comes in many varieties – meat, fish,

poultry or vegetable- of hot pepper and spice stews which are almost

accompanied by a fermented form of unleavened bread called Injera.

Injera is the national dish and it forms the base of any meal. This

large, soft, pancake-like crepe is spread out on a large tray ‘wot’

or spicy sauce is then dished out on it.

Dinners sit around the communal tray, tear off a piece of injera

(with the right hand only) and scoop up the wot or meat or

vegetables with it.

The tray on which the meal is served is placed on a mesob, a small

round table woven like a basket, with a peaked cover and a

depression on the table top where the tray is placed highly

decorative patterns are often woven into these mesobes.

For those not accustomed to such hot foods whose ingredients include

red and black pepper, cardamom, garlic and coriander, there is an

alternative: Alicha is equally delicious but a lot milder and is

usually made from chicken or lamb flavored with green pepper and

onions. Traditional Ethiopian meals are normally washed down with

tej, a type of wine made from honey, or tella which is a light, home

–brewed beer manufactured from barley. Ethiopia also produces a

range of very palatable yet inexpensive red and white wines.

Ethiopians do not traditionally end their meals with a dessert

although, if it can be found, a honeycomb dripping with honey is

often offered to sooth the heat of the wot. In any event, the end of

a meal is not complete without Buna, (the Ethiopian word for

coffee), the world’s favorites beverage which actually originated in

Ethiopia about a thousand years ago.